Risk factors, prevention and management of wound blistering: a scoping review

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Authors: Karen Ousey, Harikrishna Nair, Charmaine Childs, Rhidian Morgan-Jones, Thomas W. Wainwright, Daniel Chaverri, Mohamed Muath Adi, Sanna Kouhia, Christopher Gee, Christopher Edelman, Sara Carvalhal

Citation:

Ousey K, Nair H, Childs C et al (2025) Risk factors, prevention and management of wound blistering: a scoping review. Global Wound Care Journal 1(2): 20–32

Funding sources:

This literature review has been supported by a non-restrictive educational grant from Mölnlycke Health Care.

Declaration of competing interests:

The authors declare that they have no competing interests that could have potentially influenced the scoping review process reported in this paper. HN is the Editor-in-Chief, KO is the Academic Editor and CC is an editorial board member of the of the Global Wound Care Journal. CSW is on the Global Wound Care Journal editorial board; this did not influence acceptance.

Corresponding author:

Karen Ousey, Emeritus Professor of Skin Integrity, University of Huddersfield, Queensgate, Huddersfield, HD1 3DH. Email: kousey@omniamed..com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.63896/gwcj.1.2.20

Background: Blistering to the skin causes pain and increased risk of infection, and impacts an individual’s physical and psychological health, while increasing the burden on clinicians and healthcare systems. Blistering is recognised as a significant problem associated with surgical wounds, particularly following orthopaedic surgery, and specifically following hip and knee surgery. Healthcare professionals must adopt approaches to prevent and effectively treat blistering to optimise care and promote recovery.

Objectives:

- To identify risk factors for causation of wound blisters

- To identify the ideal dressing to prevent wound blisters

- To explore how to prevent wound blisters.

Methods: Searches were conducted in Medline, British Nursing Index (BNI), CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), Embase and Google Scholar, without date limits.

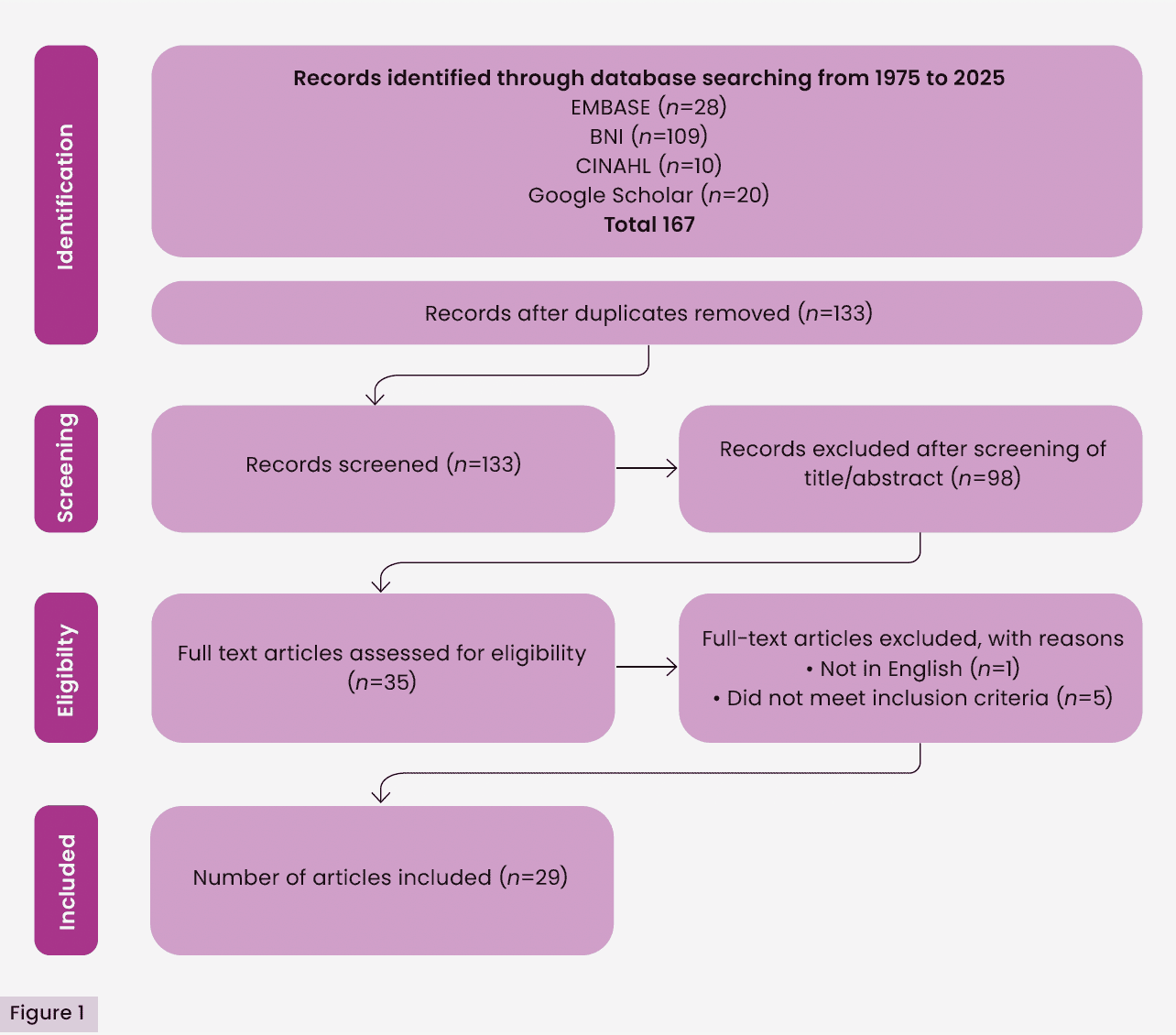

Results: Of the 177 papers located, 29 met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review.

Conclusions: There is a significant lack of research exploring risk factors that can lead to skin blistering. The research available is outdated and unclear, with a lack of consistency. Large-scale empirical international studies are needed to enable standardised guidance across all healthcare settings. Additionally, there is a need for healthcare professionals to work collaboratively to prevent skin blistering and manage wounds effectively.

In a seminal publication on blistering, Bork (1978) outlined three phases of blister formation on the skin, which can occur consecutively or simultaneously:

- “The phase of a loosening of the structure, i.e. a diminished cohesion of epidermal cells or a decreased adhesion of epidermis to the corneum

- The phase of discontinuity, of cleft formation between the keratocytes or in the different levels of the junction zone

- The phase of fluid accumulation.”

In a more recent publication, the National Library of Medicine (2024) defined blisters as “visible accumulations of fluid within or beneath the epidermis” . There are numerous causes of blistering of the skin, including: a broad spectrum of diseases; the result of a bacterial or viral infection, such as herpes or impetigo; local injury to the skin, such as burns, ischaemia and dermatitis (Diaz and Giudice, 2000). Diaz and Giudice (2000) describe how, in some diseases, blistering can occur as a primary event, presenting as tissue injury and fluid accumulation within a layer of the skin (intraepidermal, derma-epidermal junction or subepidermal) and can be due to a genetic mutation or an autoimmune response.

Skin blistering occurs when the epidermis is separated from the dermis or, due to friction on the skin. The development of blisters resulting from soft tissue injury following trauma is recognised as a significant aspect of surgical care and they can often occur in areas of the body with limited tissue coverage, such as the ankle and knee (Hoover and Siefert, 2000). Tosoundis et al (2020) describe how significant tissue trauma results in fracture blisters, which present between 6 and 72 hours post-injury, typically overlying the fracture site, causing delays to treatment and an increased risk of postoperative wound complications.

Considering the global ageing population, it is anticipated that surgical procedures including joint replacements and spinal surgery will continue to rise. The postoperative risk of wound blistering can lead to delayed healing, increased pain levels and risk of infection to wound sites due to compromised skin integrity (Bredow et al, 2015).

Skin blistering is a common problem within orthopaedics, where dressings are applied for prolonged periods of time over a joint, with static friction from the adhesion of the dressing resulting in significant shear force (Ravenscroft et al, 2006). There may be friction i.e. the dressing moving across the surface of the skin with movement. There is also significant shear/tissue deformation caused by the tight adhesion of the dressing to the skin when the tissue beneath the dressing swells resulting in tension between the dressing and the skin. This can be influenced by both the strength of the adhesion of the dressing and/or the ability of the dressing to stretch in response to both oedema and movement.

Other factors can also contribute to blistering, such as skin changes in older patients, tissue oedema following surgery, the type of dressing used, and how it is applied and removed. Medical adhesives rely on the use of a medical grade adhesive, such as acrylic or silicone adhesive, and this adhesiveness can cause skin damage both during use and on removal of the dressing. These adhesives are often used for surgical site dressings, central lines and other catheters, and can often cause skin damage when they are removed (Kim and Shin, 2021).

Skin damage resulting from the removal of adhesive products or devices (e.g. dressings, stoma products, electrodes) is known as medical adhesive-related skin injury (MARSI), generally defined as erythema and skin abnormalities that last for at least 30 minutes after removal of a medical adhesive (McNichol et al, 2013; Savine and Snelson, 2024). Kim and Shin (2021) state that soft silicone dressings have been proven to provide a gentler option for patients, particularly those with fragile skin at risk of damage, due to less risk of tearing or pain. Savine and Snelson (2024) add that silicone dressings are more cost-effective and easier to use, as no additional products are required, such as adhesive removers.

The formation of a blister removes the barrier or protection of the skin against infection; consequently, a wound blister can result in a superficial infection, which can lead to an infected prosthetic joint (Jester et al, 2000; Gupta et al, 2002).

Fast Track Protocols (Rapid Recovery Protocols) have been widely implemented in total hip and total knee replacement (TKR) surgery. Early mobilisation of the patient is one of the major goals of these protocols; however, the combination of the use of a standard dressing with early mobilisation may increase the risk of skin complications, such as irritation and blisters (Eastburn et al, 2016).

Methods

This scoping review was undertaken in accordance with the Manual for Evidence Synthesis (Peters et al, 2020) by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI, 2025). The PCC strategy (population, concept, context) was used to refine the research question:

- P=adults

- C=cause/prevention of skin blisters

- C=use of dressings.

The research question was “What evidence is available on the factors causing/preventing skin blisters and the use of dressings for effective wound management?”.

A three-step search strategy was employed:

- The searches were performed in February 2025 using the databases BNI, CINAHL, Embase and Google Scholar. All study types and methods, including grey (i.e. unpublished) literature, without time restrictions, were included.

- All titles, abstracts and index terms were then analysed for key words to ensure the relevance of each publication.

- The reference list of each publication was assessed to identify further relevant articles/publications (JBI, 2025).

Key words and data extraction

The key words used were: “wound blistering”, “blister formation”, “blister pathophysiology”, “friction blisters”, “post-surgical wound blisters”, “wound blister complications”, “negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT), Closed Incision negative pressure wound therapy (ciNPWT) and wound dressings”, “acrylic versus silicone dressings”.

Data extraction was achieved in line with the Joanna Briggs Institute template, composed of the following details: authorship, year of publication, country of publication, objectives, population and sample, method, results and findings related to blisters, and the use of dressings for effective skin management.

Results

Of the 167 results identified in the initial searches, 29 met the inclusion criteria [Figure 1]. A summary of each publication included in the review is provided [Table 1]. The number of publications pertaining to skin blistering is scarce and what is available is outdated. The three main themes emerging from the available evidence were:

- Use of negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) and closed-incision negative pressure wound therapy (ciNPWT)

- Types of dressings

- Responsibilities of healthcare professionals.

- The majority of studies identified were based on hip and knee post-surgical patients; several reported on obstetric patients, one was trauma and one general surgical patients.

Discussion

NPWT and ciNPWT

NPWT was first described by Fleischmann et al (1995) as a controllable negative pressure and constant drainage system resulting in successful surgical wound outcomes. Since then, it has been used to improve the healing of complex wounds, reducing both healing time and hospital stay (Liu et al, 2016). NPWT is used to accelerate the healing of both superficial and deep wounds through increasing blood flow and stimulating granulation, while reducing the level of bacteria and the factors preventing cell repair (Lambert et al, 2005). NPWT has also been found to reduce wound complications such as dehiscence, infection, haematoma and seroma (Huang et al, 2014). Liu et al (2018) reported that, upon treatment with NPWT, patients with an open fracture had a much lower infection rate, reduced wound recovery and healing time, reduced hospital stay and reduced amputation rate when compared with those treated without NPWT.

ciNPWT is a type of NPWT developed specifically for covering and promoting the healing of closed incisions and has been shown to reduce oedema and improve blood flow, resulting in reduced surgical site infections (SSIs) and improved overall outcomes when employed for appropriate patients (Ozkan et al, 2020). Both traditional and single-use NPWT systems can be employed for ciNPWT (Banasiewicz et al, 2019).

Despite the significant benefits of NPWT, Howell et al (2011) described how NPWT resulted in the formation of linear blisters (LBs) along the sides of dressings, reporting an LB formation rate of 63% in an NPWT test group, with patients following TKR compared with wounds treated with a sterile gauze dressing. The size of the LBs was substantial, ranging from 1cm to 10cm in length. It was reported that blisters in the experimental group occurred on intact skin between the drape and polyurethane foam.

In a study evaluating the outcomes of NPWT following open fracture surgery (n=14) (Suzuki et al, 2014), four developed skin maceration beneath the foam interface, and two experienced blistering under the adhesive drape. There was no evidence of skin necrosis or infection.

The authors concluded that NPWT had no negative effects on the wound or fracture healing. However, this finding supported previous evidence that one of the side effects of NPWT is skin blistering, which must be considered when managing wounds (Howell et al, 2011). They also suggested that the LBs could be a result of friction on intact skin at the junction of the foam and the adhesive tape, but were unable to suggest a method to prevent blistering.

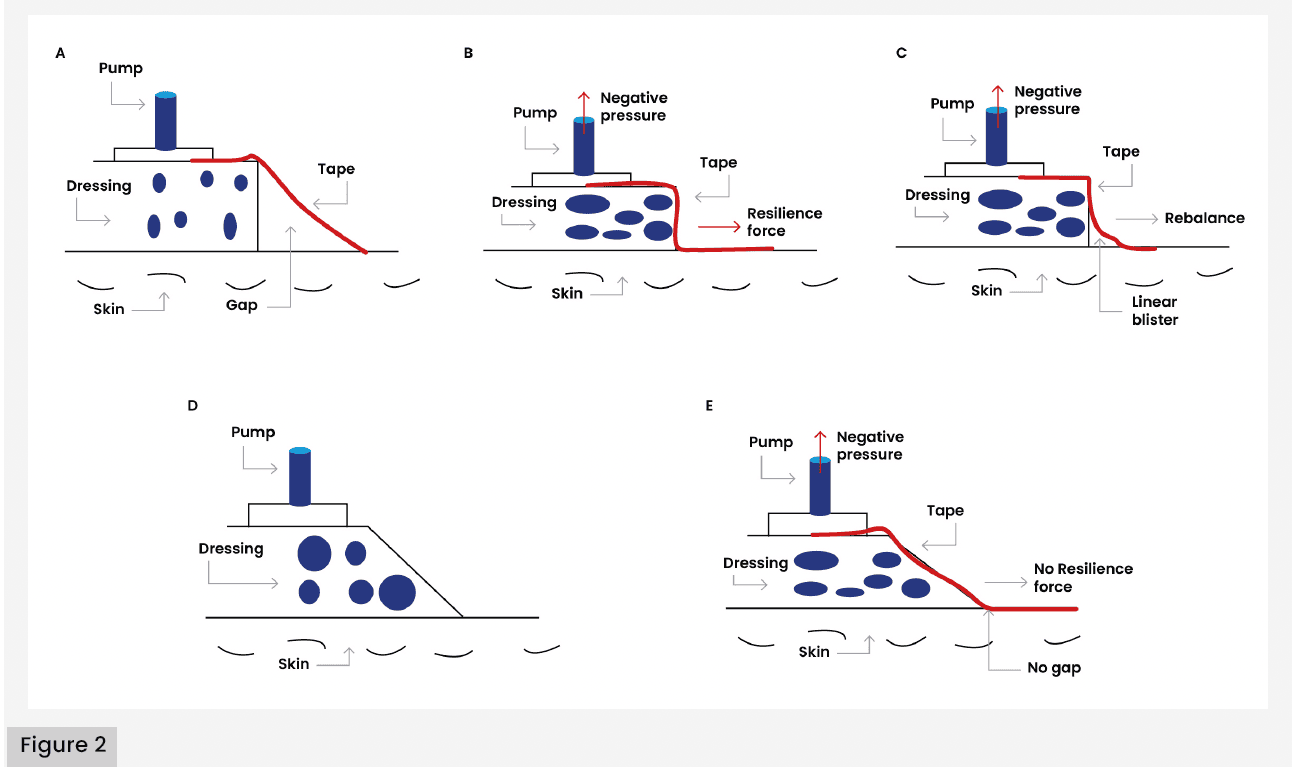

More recently, Zhang et al (2021) proposed a mechanism for LB formation [Figure 2], suggesting that mechanical and osmotic factors, such as injury or post-traumatic oedema, may compromise the dermal-epidermal junction at the injury site. This disruption creates a region of elevated permeability, facilitating fluid migration. The resulting pressure imbalance across the dermis contributes to further separation of the epidermis from the dermis, culminating in fluid accumulation and blister formation.

Based on this proposed mechanism, Zhang et al (2021) hypothesised that LB formation occurs due to the gap between the drape and the skin at the edge of the dressing. In addition to exploring LB pathophysiology, Zhang et al (2021) investigated preventative strategies through a RCT involving 53 patients with Gustilo type II and III open fractures managed with negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT), compared with a modified (trimmed) version of NPWT [Figures 2D and 2E]. The findings revealed nine LB formations in the conventional group and one LB formation in the modified group. The infection rate was higher in the conventional group (30.3%) compared to the modified group (25.9%). The length of stay was also lower for patients in the modified group at 6–19 days compared with 5–23 days in the conventional group. These findings suggest that the adapted NPWT technique may effectively reduce LB formation and postoperative complications, while supporting faster recovery and discharge.

In an Australian RCT, Manoharan et al (2016) compared the use of NPWT versus conventional dressings in a sample of 33 patients undergoing TKR. The study aimed to assess the impact of NPWT following TKR on quality of life (QoL), wound complications and cost. Twelve patients had conventional dry dressings (CDD) and 21 patients with bilateral TKR had either side randomised, receiving NPWT or CDD. The findings demonstrated no post-TKR benefit in wound healing or cost, although there were some benefits reported with NPWT relating to QoL factors, such as reduced wound leakage.

From a tertiary care medical centre in the USA, Ruhstaller et al (2017) reported outcomes from an RCT evaluating prophylactic use of NPWT to prevent wound complications in obese women following caesarean section (c-section). The RCT included 480 women; of these, 136 (28%) underwent c-section and were randomised. A total of 69 and 67 women were randomised to standard wound care dressings and NPWT, respectively. Seventeen patients were lost to follow-up during the 4-week period, leaving 58 in the standard wound care dressing group and 61 in the NPWT group for analysis. Four times as many women who received the NPWT system had a skin blister after removal of the device compared with standard wound care (13.1% with NPWT versus 3.6% with standard wound care, respectively; p=0.10).

Further research on the effectiveness of NPWT and wound healing by Giannini et al (2018) in Italy compared the effectiveness of wound healing of NPWT with a standard dressing following hip and knee revision surgery in a sample of 110 patients. Although the study outcomes did not support the use of NPWT in all patients undergoing hip and knee prosthesis revisions, NPWT was shown to be beneficial for specific patients (i.e. those at risk of wound complications). In contrast to findings from previously discussed studies (Howell et al, 2011; Suzuki et al, 2014), blister occurrence was lower in the NPWT group (Giannini et al, 2018).

The effectiveness of ciNPWT has also been compared with an occlusive silver-impregnated dressing in a US RCT (Doman et al, 2021) across a sample of 130 post-TKR patients. The findings revealed that the ciNWPT group had fewer incisional wound complications (6.9% versus 16.2%) but significantly more non-incisional wound complications (16.9% versus 1.5%). Among high-risk patients undergoing TKR, ciNWPT reduced incisional wound complications, although an increase in dressing reactions were noted but the clinical impact was minimal.

A meta-analysis of level I studies aimed to determine the effects of ciNWPT on the risk of SSIs and wound complications following total joint arthroscopy (Ailaney et al, 2021). They concluded ciNWPT decreases SSI risk and length of hospital stay when compared to traditional standard dressings; however, use of ciNPWT did increase non-infectious wound complications, such as blisters, seroma, haematoma, persistent drainage and wound edge necrosis. In terms of the risk of blistering, ciNWPT was associated with a greater than 12-fold increase of wound blistering post-TKR. No significant differences were detected in rates of overall wound complications, infection, seroma and length of hospital stay. The authors emphasised the need for additional randomised controlled trials to draw definitive conclusions about the use of closed-incision negative pressure wound therapy (ciNPWT) following primary total joint arthroplasty.

In a literature review exploring risk factors for SSIs, Willey et al (2016) identified obesity, diabetes, tobacco use and prolonged surgical time as the most common risk factors and called for surgeons to assess the risks of SSIs alongside other risks of morbidity. Willey et al (2016) recommend selected use of ciNWPT for patients with one or more comorbidities.

Dillon et al (2007) investigated the mechanical demands of hip and knee surgery wounds by quantifying skin movement during joint flexion. The study compared the extensibility of four dressing types — a hydrocolloid, a traditional adhesive and two occlusive film dressings — against the strain observed in TKR wounds. Results indicated that TKR wounds exhibited dynamic morphology with strain exceeding 20% during normal knee flexion. While the hydrocolloid and occlusive dressings demonstrated sufficient extensibility to accommodate this movement, the traditional adhesive dressing did not. The authors suggested this may explain the high blister rates with some dressings.

Types of dressings

Ousey et al (2011) recommend that dressings should provide a warm, moist healing environment that does not damage the peri-wound area and result in blistering. This discussion paper emphasises that protection of the peri-wound area is essential and can be achieved through choosing the correct dressing, which does not adhere to the surrounding skin and is flexible, while being easy to apply and remove. Various studies have compared different types of dressings to determine the incidence of blistering on postoperative wounds. A literature review by Collins (2010) to determine how postoperative dressings affect wound healing found that there was no preferred treatment, and a range of dressings were recommended to reduce the risk of blistering. A further literature review and cross-sectional study (Siddique et al, 2011) evaluating the effectiveness of hydrocolloid dressings for postoperative hip and knee wounds found that hydrocolloid dressings (DuoDERM®) helped to prevent SSIs and blister formation in patients undergoing lower-limb orthopaedic surgery.

In a two-phase study in the UK, Gupta et al (2002) evaluated the incidence of periwound blistering to determine whether there was any association with choice of wound dressing. Phase one evaluated three dressing types: Microdon, Mepore® and spirit-soaked gauze held with Mefix® applied to 100 patients following hip and total knee replacement or primary/revision total knee replacement. Of the 41 patients given Microdon dressings, 16 (39%) developed blisters. Five of the 23 patients (21.7%) given Mepore® developed blisters. None of the 16 patients given spirit-soaked gauze held with Mefix® developed blisters (Gupta et al, 2002). The authors assumed that blistering was caused by friction between the skin and dressing during joint movement. As a result, phase two was undertaken with staff being advised not to stretch the dressings pre-application. The same dressings were applied to a further 100 patients who had undergone hip operations and primary/revision total knee replacements. In phase two, Gupta et al (2002) reported 10 of the 58 patients (17.2%) given Mepore dressings and four of the 22 patients (18.2%) given Microdon developed blisters. Again, none of the 20 patients given spirit-soaked gauze with Mefix developed blisters. The authors concluded that not stretching Mefix or Mepore made no significant difference to the development of wound blistering; however, for Microdon, blistering was more than halved.

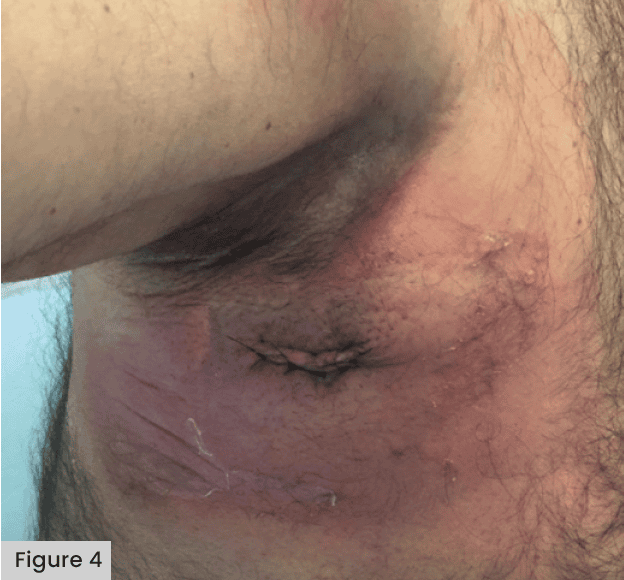

See Figures 3 and 4, demonstrating blistering following application of a Mepore-like dressing.

Abuzakuk et al (2006) undertook an RCT in the UK comparing a Hydrofiber® (AQUACEL®) dressing with a central pad (Mepore) following total hip arthroplasty (THA) or TKA. Among the 61 patients included in this study, there was a significant reduction in the requirement for dressing changes before 5 days in the Hydrofiber group (43% versus 77% with central pad) and fewer blisters (13% versus 26% with central pad). This indicated a potential role for Hydrofiber dressings in the management of arthroplasty wounds. In an RCT in Germany, Bredow et al (2015) compared the risks of postoperative blistering and wound infections across a sample of 150 patients. Comparisons were made with Mepore Pro. Mepilex Border and Hypafix® transparent. Blistering was significantly lower with Mepilex Border (3%) than Mepore Pro (59%) and Hypafix (61%). The time between surgery, blister re-occurrence and the number of dressings used was also significantly lower for the Mepilex Border group. The authors concluded that the dressing with a silicone adhesive (Mepilex Border) significantly reduced the prevalence of blistering following hip surgery.

Other studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of Opsite® Post-Op dressings in reducing blisters postoperatively. An RCT in the UK (Cosker et al, 2005) compared three dressings (PRIMAPORE™, Tegaderm® with pad and Opsite Post-Op) across a sample of 300 post-surgical patients (TKR, total hip replacements, hip hemi-arthroplasty, dynamic hip screw, tibial nailing and femoral nailing). The findings reported a significantly lower incidence in blistering with the application of Opsite, despite the patients being older with friable skin. It was believed that this was due to the elasticity of Opsite. The lack of elasticity in dressings has been found to increase the risk of blistering (Blaylock et al, 1995). Jester et al (2000) compared Opsite Post-Op dressings with Mepore dressings across a sample of 169 patients following total hip and knee replacements, revealing four out of 28 patients developed blisters with Mepore compared with eight out of 88 with Opsite Post-Op dressings. This result supports previous findings that a lack of elasticity of dressings, coupled with oedema, contributes to skin blistering. A later study by Leal and Kirby (2008) also supports the use of Opsite Post-Op dressings in preference over Mepore: in an RCT with 67 women post-hysterectomy, no blisters were found in the patients treated with Opsite dressings, compared with eight in the group treated with Mepore dressings.

Ravenscroft et al, (2006) in their RCT compared AQUACEL dressing covered with Tegaderm with CUTIPLAST™ across a sample of 183 patients following hip and knee surgery. The findings revealed that, compared with CUTIPLAST, AQUACEL and Tegaderm dressings were 5.8 times more likely to result in a wound without complications: approximately, 22.5% of patients with Cutiplast developed blistering, compared with 2.4% of patients with AQUACEL and Tegaderm.

Hahn et al’s (1999) comparative study, determining wound complications following hip surgery in patients treated with compression spica wrap versus those treated with traditional taping methods, revealed a significantly lower incidence of blisters and drainage in the group using the compression wrap dressing. There was no higher incidence of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or infection associated with the wrap. The authors concluded that compression wraps should be used to reduce wound complications and blistering. However, no further published studies could be located that refer to the use of wraps.

In an Australian RCT, Lawrentschuk et al (2002) compared the rate of wound blisters in two commonly used dressings (non-adherent absorbable [NAA] and paraffin tulle gras [PGT]) among 50 patients following hip surgery. The findings revealed a significant difference within the groups: 64% patients in the NAA group developed blisters, compared with only 8% in the PGT group.

Cole et al (2020) performed a RCT to compare incidence of blistering between postoperative dressings and postoperative dressings plus skin protection across a sample of post-spinal surgery patients: 92 patients received a postoperative dressing, while 93 patients were given a barrier film underneath the dressing. It was noted 15% of participants in the treatment group and 15% of participants in the control group developed a postoperative skin injury (p=0.98) developed erythema, soreness or blistering postoperatively on the skin under the border of an adhesive dressing. Cole et al (2020) called for further research to determine the causes of dressing-related skin blisters in postoperative patients.

A meta-analysis comparing wound dressings after hip/knee arthroplasty demonstrated that an antimicrobial dressing is optimal for preventing infection (Kuo et al, 2021); the authors also warned that, if NPWT is used, surgeons must be aware of the increased incidence of skin blistering formation [Figure 5]. The data from 21 studies, encompassing 12 dressing types applied across 7,293 total joint arthroplasties identified the highest incidence of blisters occurred when using negative pressure wound therapy (OR 9.33; 95% CI 3.51-24.83) versus gauze. They recommended further research focusing on alginate versus hydrofiber and hydrocolloid dressings to determine the optimal dressing to reduce blisters.

Responsibilities of healthcare professionals

A two-stage Delphi study (Ousey et al, 2012) reinforced the notion of easy application and removal of dressings to prevent blistering, recommending that dressings remain in place for as long as possible, providing no leakage or signs of infection were present.

Several studies highlight the importance of the knowledge and skills required for healthcare professionals in managing surgical wounds to ensure the correct technique and dressing choice are used to reduce the risk of blistering. This discussion paper recommends that the wound’s location, method of closure, level of exudate and dressing wear time should be considered when selecting dressings. A literature review by Eastburn et al (2016) emphasised the need for a multidisciplinary approach to manage wounds effectively, promote rehabilitation and prevent blistering, specifically recommending that physiotherapists collaborate with other members of the multidisciplinary team when managing wounds.

The role of the multidisciplinary team in postoperative wound management and blistering was also highlighted by Heller et al (2015); their prospective study on 135 patients following TKR compared the incidence of blisters in 200 patients with the tourniquet released immediately after wound closure in theatre. The findings revealed that releasing the tourniquet early, prior to dressing application, reduced the incidence of blistering following TKR: the incidence of blistering was 7.5%, compared with 2.2% in the early release group. This emphasises how important it is for all healthcare professionals, including surgeons and theatre staff, to understand the management of wounds and risk of blistering. Following a literature review on dressing choice and outcomes after hip and knee arthroplasty, Tustanowski (2009) called for multidisciplinary action, recommending that wound management commences in theatre with a collaborative approach, while also calling for more large-scale RCTs to determine the effectiveness of dressings. This was later supported by Willey et al (2016), who recommended that surgeons assess the risk of SSI alongside morbidity when considering postoperative wound management.

While most of the literature focuses on blistering following orthopaedic surgery, Sanusi (2011) was the first to publish a report on wound traction blistering following laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the UK. This case report, based on a 78-year-old healthy male, described how large vesicles were observed following removal of the dressings around the epigastric port incision. Indentations created by the dressing and skin traction raised questions about the technique of application. This study demonstrated the importance of the correct application of wound dressings and how incorrect techniques, such as stretching adhesive dressings, can result in extensive blistering, which is otherwise fully preventable. The findings highlight the importance of comprehensive education for healthcare professionals in wound management. Specifically, the study identifies the need for targeted training in appropriate dressing selection, correct application techniques, and the potential risks associated with both material choice and procedural variation.

Limitations

This scoping review is subject to several limitations. While multiple databases were searched, the scope did not extend to all potentially relevant sources, thereby introducing the possibility of missed literature. Additionally, the included studies were not subjected to formal critical appraisal prior to inclusion, which may affect the interpretability and overall strength of the evidence base. The majority of studies were outdated, with many conducted over a decade ago and earlier. Given the substantial advancements in dressing technologies (e.g. modern silicone-based materials), application methods, and peri-operative protocols in recent years, the generalisability of earlier findings may be restricted and may not reflect current clinical practice.

Conclusion

The review highlighted there is a significant lack of data available in the published literature on this topic. A lack of routine follow-up and poor post-discharge data collection makes it likely that this issue is under-reported. The data available are also heterogenous, with very few RCTs, making meta-analysis impossible. Further data are required, with the addition of better postoperative reporting, perhaps through the use of digital technology, to be able to fully understand the incidence of blistering, the impact on patients’ wounds and their overall surgical outcome, and which dressings are protective against both blistering and SSI.

This scoping review examined existing research on the causes and prevention of skin blistering, particularly in postoperative patients. Despite some international contributions, most papers were from the UK. There is a notable lack of recent, high-quality literature, particularly expert opinion pieces, RCTs and case studies. Evidence relating to risk factors and dressing use is inconsistent and often difficult to interpret, suggesting a lack of consensus.

To support clinical decision-making and improve patient outcomes, there is a need for large-scale empirical studies, particularly RCTs, to explore both the aetiology and prevention of skin blisters. Clear, consistent guidance is essential to enable healthcare professionals across settings to implement safe, evidence-based practices. Inadequate blister prevention not only contributes to patient pain and discomfort, but also increases the risk of SSIs, joint infections, and prolonged hospitalisation. Given the rising surgical demand within an ageing population, addressing these knowledge gaps should be considered a research priority.